What began as a simple initiative to help Hindu pilgrims during the annual Kanwar Yatra has now morphed into a deeply polarising campaign that critics argue reeks of subtle communal profiling and economic marginalisation—especially targeting Muslim vendors along the 540-km stretch across Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and Uttarakhand.

Under the guise of ensuring “spiritual purity” for devotees, saffron-coloured “Sanatani Vyaparik Sansthan” stickers with slogans like “Garv se kaho, hum Hindu hain” are now pasted prominently on shops that pledge to serve only vegetarian food. Spearheaded by the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP) and supported by local Hindu volunteers, the campaign is portrayed as a mere guide for religiously observant Kanwariyas. But on the ground, the consequences are anything but benign.

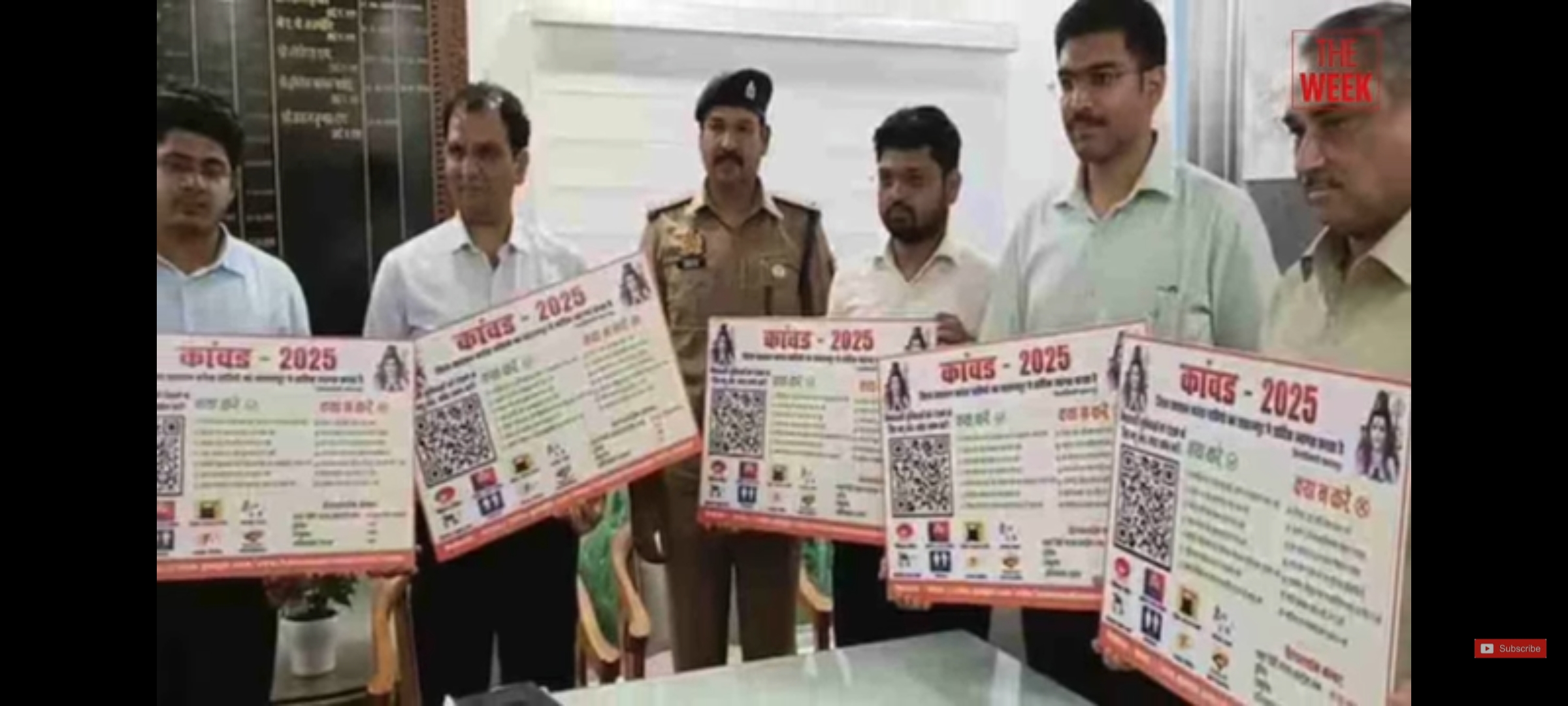

Simultaneously, the Uttar Pradesh government’s mandate requiring all eateries along the Yatra route to display QR codes linked to the Food Safety CONNECT app—detailing the name of the owner, FSSAI status, food category, and hygiene records—has only compounded fears of institutionalised profiling. For many, especially Muslim shopkeepers, this seemingly neutral digital system has become a new form of exclusion.

Wasim Ali, a vegetarian dhaba owner in Bijnor, shares his ordeal: “I serve only veg food. My shop is clean and licensed. But pilgrims scan the QR, see my name, and just walk away.”

It’s a growing pattern in western UP’s mixed-population towns like Muzaffarnagar, Moradabad, and Hapur. Vendors with Muslim names say their sales have plummeted, not because of food quality or hygiene, but because of religious identity being subtly used as a filter.

Legal experts warn that this combination of religious stickers and QR-linked identity checks is creating a climate of soft boycotts—informal yet devastating. Advocate Zoya Khan calls it “digital vetting without due process.” She adds, “The QR codes are not inherently communal, but when paired with a campaign like ‘Sanatani only,’ they become tools of indirect discrimination. It’s a silent segregation.”

In Meerut, one sweet shop owner confessed he put up the Sanatani sticker not by conviction, but necessity. “No one forced me. But when I didn’t have the sticker, pilgrims stopped coming. They asked for it. It felt like a test of faith—one that I never signed up for.”

Women vendors are also being affected. Shabnam Javed, who runs a vegetarian snack stall in Muzaffarnagar, says, “I never served meat. But that’s not enough. My name now defines the purity of my food. This isn’t trust, it’s religious coercion.”

While the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) and VHP maintain this is not a communal campaign, the symbolism and ground realities speak differently. “Even at home, during fasting, we ensure food purity,” says RSS pracharak Bholendra. “Helping pilgrims eat right is not communal.”

But civil society groups see this as part of a wider saffronisation project. The use of religious identifiers, moral policing of food habits, and digital tracking of ownership have laid the groundwork for excluding Muslims not just from a religious event but from daily economic life.

Moreover, such moves blur the line between governance and ideology. When a state-led digital system converges with a religious-purity campaign, the risk of normalising exclusionary practices becomes dangerously real.

Many observers argue that these developments are not accidental but strategic—an effort to shape public spaces into ideological battlegrounds. The Kanwar Yatra, once a colourful and inclusive cultural event, is now marked by quiet fear, identity policing, and economic suffocation.

As the Yatra concludes this season, the VHP claims the Sanatani sticker campaign will end. But social scientists and activists warn that the mindset it has fostered won’t fade. Once normalized, religious tagging becomes a tool for everyday marginalisation.

In an India that aspires to unity in diversity, such campaigns fracture the very spirit of coexistence. A vegetarian dish should not need a religious label, and a vendor’s name should not decide his right to earn a livelihood.