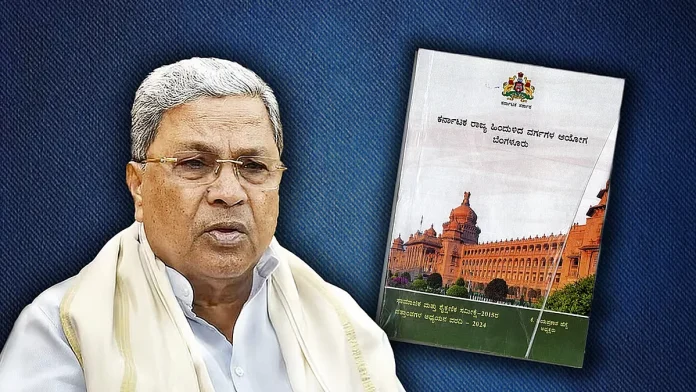

Bengaluru : In a move drawing sharp criticism from academics, social activists, and political observers, the Siddaramaiah-led Congress government in Karnataka has officially scrapped the 2015 Social and Educational Survey—popularly dubbed the “caste census.” This decision, made under mounting pressure from powerful caste lobbies such as the Lingayats and Vokkaligas, is being described as a major win for dominant caste groups that have historically opposed caste-based data collection, reported the Newsminute.

The Kantharaj Commission’s survey, which had covered over 94% of Karnataka’s population, was intended to compile comprehensive data on the socio-economic and educational status of various caste groups. Experts say the survey held the potential to reshape affirmative action and welfare schemes based on actual social backwardness rather than historical assumptions.

Despite this, influential caste groups like the Akhila Bharata Veerashaiva Mahasabha, Karnataka Rajya Vokkaligara Sangha, and Akhila Karnataka Brahmin Mahasabha launched sustained campaigns discrediting the survey as “unscientific” and alleging underrepresentation.

Kenchappa Gowda, President of the Karnataka Rajya Vokkaligara Sangha, dismissed the survey’s authenticity based on anecdotal reports from acquaintances who claimed they weren’t surveyed. Similar remarks came from Congress MLA Shamanur Shivashankarappa, who heads the Veerashaiva Mahasabha.

Observers note that although the survey wasn’t a census in the statistical sense, its scope was far larger than previous backward class commissions, with data collected from over 95% of households.

Professor A. Narayana of Azim Premji University criticized the government’s handling of the issue, stating that the term “caste census” was irresponsibly interchanged with “survey” over the past decade, leading to public confusion.

Sections 9(1) and 9(2) of the Karnataka State Backward Classes Commission Act, 1995, legally mandate such surveys every 10 years. The 2015 survey, though now a decade old, remains the only such attempt in that period. Siddaramaiah has promised a new survey, citing the age of the existing data.

Critics like journalist Dinesh Amin Mattu allege that the state’s mainstream media—dominated by Brahmin-owned publications—have largely echoed dominant caste concerns while failing to question the government’s retreat or advocate for public access to the survey data.

“The media failed to ask why public money was spent on a survey whose findings are kept hidden. Economic conditions may evolve, but caste does not change in a decade,” Mattu said.

Though the raw data—digitised and searchable—is locked within government departments, no public or academic access has been granted. The data, spread over 40 volumes, contains information on land ownership, education levels, occupational profiles, and more, and could offer a critical resource for policy and research.

KN Lingappa, a former Karnataka State Backward Classes Commission member, said the real reason for rejecting the survey is the fear among dominant castes that data could challenge their political clout.

The opposition to caste-based surveys is not new. Since the 1960s, Lingayats and Vokkaligas have resisted inclusion in backward class lists or protested their exclusion from them—depending on which offered political or social advantage. While Mysore’s 1921 Miller Committee reserved 75% of opportunities for backward classes (including Lingayats and Vokkaligas), later commissions such as the Naganagouda (1961), Havanur (1975), Venkataswamy (1986), and Chinnappa Reddy (1990) faced backlash whenever dominant groups were excluded or categorized differently.

The state’s political leadership has often buckled under pressure—from burning reports in the Assembly to street mobilizations of over 100,000 protestors. The fallout has been consistent dilution of commission recommendations to accommodate political interests.

In 1994, CM Veerappa Moily formalized the present five-category reservation system, which effectively reinstated Lingayats and Vokkaligas under new classifications despite earlier data suggesting they were not socially or educationally backward.

While Siddaramaiah has promised a fresh survey, critics argue that discarding the existing one is an affront to both transparency and constitutional obligations. Many call for immediate public release of the 2015 survey data, asserting that hiding caste realities perpetuates social inequity.

“Public money was spent on the survey. People have the right to see the truth, no matter how old the data is,” said Dinesh Amin Mattu.