The Langas, Manganiyars, and Dagars: Rajasthan’s Musical Bridge Across Cultures

– Dr. M. Iqbal Siddiqui

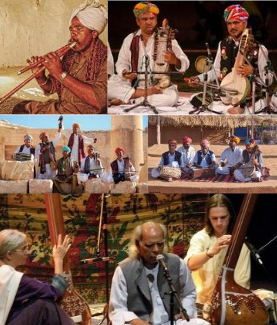

In the shimmering expanse of Rajasthan’s Thar Desert, where golden sands stretch endlessly under a relentless sun, the haunting melodies of the Kamaicha and Sindhi sarangi rise like mirages of the past. For centuries, the Langas and Manganiyars – two hereditary Muslim musician communities, have been the custodians of this enchanting soundscape. Their music, a vibrant tapestry of Sufi devotion, Hindu folklore, and desert lore, embodies the region’s profound cultural syncretism. As these artists perform at global venues from Carnegie Hall to the Cannes red carpet, they not only preserve an ancient legacy but also bridge divides in an increasingly polarised world.

Roots Steeped in Legend and History

The origins of the Langas and Manganiyars trace back to the Dholi or Mirasi caste, ancient wandering musicians and genealogists of North India. Emerging as distinct communities around the 19th century, they branched from this shared heritage, settling primarily in Rajasthan’s Barmer and Jaisalmer districts, with echoes extending into Pakistan’s Sindh region.

Legends infuse their identity with poetic depth. The Manganiyars’ name derives from “mangan” (to beg) and “har” (garland), rooted in a tale from 570CE where Bibi Fatema bestowed a necklace upon a Mirasi named Mangan. The Langas, meaning “song-givers,” are similarly evocative, possibly linked to their melodic gifts or instruments. Their gradual conversion to Islam, influenced by Sufi saints like Khwāja Muʿīn ud-Dīn Chishtī in the 12th century, blended seamlessly with pre-existing traditions, creating a faith that honours both Islamic mysticism and Hindu devotion.

Demographically, these endogamous groups form part of Rajasthan’s Muslim minority, numbering around 4.8 million as per the 2001 census. Villages like Barnawa Jageer and Lakhe ki Dhani teem with talent – Barnawa alone boasts over 200 Langa musicians. Yet, despite their artistic renown, they have endured social marginalisation, inheriting the “low caste” stigma from their Dholi ancestors.

Instruments That Sing of the Desert

At the heart of their art lie instruments as unique as the desert itself. The Manganiyars are masters of the kamaicha, a rare 17-stringed bowed wonder crafted from mango wood, goat skin, and a mix of intestine, copper, and steel strings – some melodic, others sympathetic for resonance. Gazi Khan Barna, for instance, plays a 450-year-old heirloom, underscoring the instrument’s endangered status.

The Langas, divided into sub-clans, showcase equal ingenuity. The Surnaiya Langas excel with wind instruments like the Surnai, Algoza, Satara, and Murli, evoking the windswept dunes. The Sarangia Langas favour the Sindhi Sarangi, whose voice-like timbre captivates listeners. Shared across both communities are the rhythmic dholak (drum), clacking khartal (wooden castanets), jaw-harp morchang, and versatile harmonium, blending to create performances that pulse with life.

A Multilingual Repertoire of Tales and Devotion

Language is the soul of their music, with Marwari as the bedrock. Yet their songs weave a multilingual mosaic, incorporating Sindhi, Punjabi, Saraiki, Dhatki, Braj Bhasha, and Hindi. This reflects their cultural crossroads, adapting lyrics to patrons’ backgrounds.

Their repertoire is a treasure trove: Sufi kalaams invoking divine love, Hindu bhajans and mythological epics, romantic ballads like Umar-Marvi, Heer-Ranjha, and Moomal-Rana, and heroic tales of patrons’ genealogies. Tied to ragas suited to times of day or occasions, performances often begin with an improvised duha (couplet), transforming music into a living archive of oral history.

Patronage, Challenges, and Resilience

Historically, the jajmaani system sustained them: hereditary service to patrons in exchange for sustenance. Langas typically served Sindhi Muslim families, while Manganiyars catered to Rajput and Hindu households, performing at births, weddings, funerals, and festivals. This bond fostered deep syncretism – Muslim artists singing Hindu hymns with such authenticity that audiences often mistake their faith.

The decline of princely states eroded this patronage, pushing many towards migratory performances and global tours. Economic hardships persist, with limited support and village-level exclusion. As Manganiyar singer Manjoor Khan poignantly notes: “Hindu Rajputs have kept our legacies alive; they have protected us and kept our art living and thriving. For years, we have been singing for them.”

Yet resilience shines through. Ethnomusicologist Komal Kothari (1929-2004), a Padma Bhushan recipient, revolutionised their fate by founding Rupayan Sansthan in 1960. His efforts documented and promoted their music, bridging village lanes to international stages. Today, over 20,000 hours of recordings from 1980-2003 are being digitised in collaboration with the Archives and Research Centre for Ethnomusicology and the American Institute of Indian Studies, preserving epics in Marwari, Sindhi, and beyond. Training camps at the Arna Jharna Museum nurture young talents, ensuring cross-learning between Langas and Manganiyars.

Global Stars and Cultural Icons

Modern exponents have propelled this heritage worldwide. Mame Khan, a Manganiyar luminary, has graced Carnegie Hall and Cannes, declaring: “The root of Indian music lies in its folk music… I am trying my best to keep it alive and enhance its reach.”

He adds of his Cannes appearance: “I am honoured to represent the culture and tradition Rajasthan has to offer through music and art.”

Ustad Anwar Khan Manganiyar, awarded the Padma Shri in 2024, fuses classical ragas with folk and Sufi elements, contributing to Bollywood hits like “Ghoomar” in Padmaavat. Sakar Khan, another Padma Shri recipient (2012), was a kamaicha virtuoso whose legacy endures through his family.

Festivals like Pushkar Camel Fair and Jaisalmer Desert Festival draw tourists, while digital platforms offer new avenues. Intriguingly, Manganiyars’ devotion in Hindu songs often leads to misconceptions about their identity, and the kamaicha remains one of the world’s rarest instruments.

The Dagar Family

The Dagar family stands as the foremost custodian of the Dagar-bani style of Dhrupad, the most ancient form of Hindustani classical music. Their lineage traces back nearly five centuries to Brij Chand of Daguri, near Delhi, and possibly to Swami Haridas’s era, the guru of Tansen. The foundational figure of the gharana was Baba Gopal Das, a Hindu musician who embraced Islam during the reign of Emperor Muhammad Shah, thereafter known as Imam Baksh Khan. From that moment onward, the family not only remained steadfast in their Islamic faith but also flourished musically, producing generation after generation of gifted singers. Their history embodies a unique blend of spiritual devotion and artistic perseverance, even in times of cultural adversity.

The family’s prominence grew under stalwarts such as Behram Khan (1753-1852), a celebrated singer, scholar, and musicologist associated with the Jaipur court. His grandnephews, Allah Bande Khan (1845-1927) of Alwar and Zakiruddin Khan (1840-1932) of Udaipur, were hailed as a vocal duo likened to “the sun and the moon” in the world of Dhrupad. Their contrasting yet complementary styles gave birth to the meditative and stately alaap that has since defined the Dagar tradition. Allah Bande Khan’s descendants, especially Nasiruddin Khan (1895-1936), refined this legacy with extraordinary technical command, while his brother Rahimuddin Khan was the first to adopt “Dagar” as a patronymic surname – soon embraced by the entire family.

Through the 20th century, the Dagar family, notably the Senior Dagar Brothers, Ustad Nasir Moinuddin (1921-1967) and Ustad Nasir Aminuddin (1923-2010), along with the younger Ustad Zahiruddin (1932-1994) and Ustad Faiyazuddin (1939-1989), brought Dhrupad to national and international prominence. Their recitals upheld the dignity of this art form even during periods when patronage waned and audiences diminished. Parallelly, Ustad Zia Mohiuddin Dagar (1929-1990) elevated the Rudra Veena to global acclaim, while training disciples who carried the tradition into the next generation. The Gundecha Brothers, among their foremost students, remain modern torchbearers of this spiritual and austere art.

Despite historical adversities, the Dagars preserved their musical identity, nurtured their faith, and shared their art with openness across regions and communities. Today, their legacy continues to embody Rajasthan’s role as a crucible of classical music, where devotion and discipline fused into a living heritage of both Islam and art.

A Resilient Harmony in a Modern World

The Langas, Manganiyars, and the Dagar family are not merely performers but custodians of Rajasthan’s syncretic heart, weaving together threads of Sufi mysticism, Hindu devotion, and desert lore into a timeless musical tapestry. In an era of division and rapid change, their art stands as a testament to the enduring power of cultural unity, resonating from the Thar’s golden sands to stages worldwide. By embracing their performances, supporting preservation efforts like Rupayan Sansthan, or engaging with their digital archives, we help sustain a legacy that celebrates shared humanity. Their melodies, carried by the desert winds, continue to inspire, reminding us that true heritage thrives where tradition, faith, and resilience converge.