– Maliha Fatema Zakir

In the long history of Himalayan tragedies – from Kedarnath’s devastating floods to Chamoli’s glacier burst – August 5 will be remembered as yet another dark chapter.

Nestled deep in the Uttarkashi district of Uttarakhand, the quiet village of Dharali, home to about 900 people, was jolted awake by a sudden, violent wave of destruction. In mere seconds, a lush riverside landscape turned into a graveyard of mud, rock, and splintered wood.

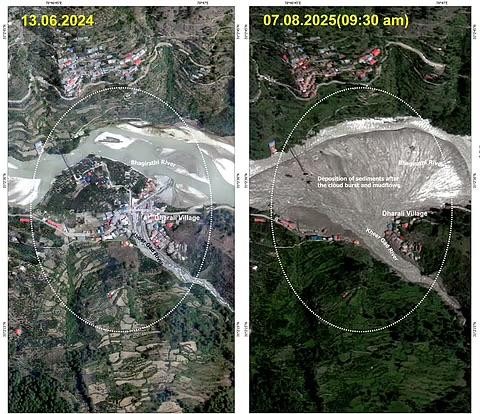

Houses were ripped from their foundations. Hotels vanished under thick layers of debris. Entire buildings stood buried up to their rooftops. By the time it was over, an estimated 360 million cubic metres of debris had hurtled through Dharali, rewriting the village’s geography in a blink.

A Village 2600 metres Above

Dharali sits 2,600 metres above the sea level, along the Bhagirathi River on the Himalayan slopes of northeastern Uttarakhand state. The village serves as a domestic tourist destination and a common stopover for Hindu pilgrims travelling to the sacred temple town of Gangotri. According to The Indian Express, Dharali and nearby villages were celebrating a religious festival that week.

Adding to its vulnerability, many houses, hotels, and other structures line both sides of another river that originates from the snout of a glacier at 6,700 metres and flows for about seven kilometres before merging with the Bhagirathi. This scenic setting is also a precarious one.

Adding to its vulnerability, many houses, hotels, and other structures line both sides of another river that originates from the snout of a glacier at 6,700 metres and flows for about seven kilometres before merging with the Bhagirathi. This scenic setting is also a precarious one.

Was it Sky or the Ice?

The Cloudburst Hypothesis

The initial assumption was that a cloudburst had triggered the catastrophe. A cloudburst occurs when warm, moist air from lower altitudes rises up the mountain slopes, meets cooler air, and forms a massive storm cloud. Inside the cloud, moisture droplets grow heavier, but strong upward air currents keep them suspended. When the cloud can no longer hold the weight, it bursts, releasing torrential rainfall of at least 100mm per hour over a 20–30 sq km area. This sudden downpour often results in flash floods and landslides.

The Glacier Collapse Hypothesis

However, data soon challenged this theory. According to meteorologist Rohit Thapliyal, “Only very light to light rain was observed in the affected area over 24 hours. The highest rainfall recorded anywhere in Uttarkashi was merely 27mm at the district headquarters.” This amount was far too low to unleash a flood of such magnitude.

Experts began pointing to a Glacial Lake Outburst Flood (GLOF) or glacier burst. A GLOF happens when a lake formed by melting glacier water suddenly bursts through its natural moraine or ice dam. This sends a massive wave of water, ice, mud, and rocks downstream, destroying everything in its path. Triggers can include heavy rain, avalanches, landslides, earthquakes, or melting within the dam itself.

In Dharali’s case, experts suggest the cause may have been a combination of rainfall and falling debris.

As one scientific note revealed, “The location of the lake and drainage pattern indicate potential hydrological connectivity to Dharali via the Kheer Ganga rivulet, which descends roughly 2,660 metres over 11.38km before joining the Bhagirathi River.”

Another scientist added, “There is a glacier right above Kheer Gad stream; a sudden release of water, either from a glacial lake outburst or glacier burst, could lead to a high-energy flash flood, similar to the Raini disaster in Chamoli in Feb. 2021.”

This is not an isolated threat. NDMA has identified 13 glacial lakes in the region as high risk – five of them are considered “extremely dangerous” for their potential to cause disastrous floods.

Climate Change: A wake up call

Climate change has emerged as a major amplifier of natural disasters. The Indian subcontinent’s monsoon is driven by warm air from the Arabian Sea. But climate change has altered global weather patterns: rising Mediterranean temperatures are pulling hotter air further north and forcing more moisture towards the Himalayan foothills, leading to heavier rainfall.

Global warming is also increasing the number and volume of glacial lakes as glaciers retreat. The plight of Dharali is not an isolated tragedy – it is a symptom of a far greater wound inflicted upon our planet. Rising global temperatures, driven by human activity, are accelerating the melting of glaciers, altering rainfall patterns, and intensifying extreme weather events. What unfolded here in the Himalayas is unfolding in different forms across the globe – from floods swallowing villages in Pakistan and Bangladesh, to wildfires ravaging forests in Greece, Canada, and California, to droughts crippling farmlands in Africa.

In Dharali, the changing climate is written in the language of receding snowlines, unpredictable monsoons, and glacial lakes swelling to dangerous levels. The village’s devastation was not born overnight – it’s the cumulative result of decades of unchecked industrialisation, deforestation, and fossil fuel dependence. Scientists have warned us for years: warming in the Himalayas is happening at twice the global average. Here, climate change is not a theory – it’s an uninvited, unstoppable guest at every doorstep.

Yet, this is not only Dharali’s fight. Every plastic bottle discarded into a river, every forest cleared for short-term profit, every tonne of carbon released into the atmosphere pushes another community closer to disaster. The Earth’s alarm clock is ringing, and it will not wait for us to hit “snooze” again.

We need urgent and unified action – not just from governments, but from each individual. Plant trees. Conserve water. Reduce waste. Demand clean energy policies. Support sustainable businesses. Small actions, multiplied across millions, can tip the balance. Climate change is a human-made crisis – but that means it is also a human-solvable one. Dharali’s tragedy is a warning; whether it becomes our turning point or just another entry in the growing list of disasters depends on what we choose today.

Recent satellite images from ISRO and NRSC suggest that the Kheer Ganga river, due to the disaster, has now reverted to its ancient course – once occupied by settlements – before meeting the Bhagirathi. Instead of curving as it usually does, the river surged straight through buildings and roads, reclaiming its old path.

Recent satellite images from ISRO and NRSC suggest that the Kheer Ganga river, due to the disaster, has now reverted to its ancient course – once occupied by settlements – before meeting the Bhagirathi. Instead of curving as it usually does, the river surged straight through buildings and roads, reclaiming its old path.

Human Negligence

What happened in Dharali was not a freak accident – it was a disaster foretold. For years, scientists had been raising alarms about the dangers posed by high-risk glacial lakes in the Himalayas. As far back as 2014, satellite imagery and field surveys had identified the very lake that would eventually burst, noting its unstable moraine walls and rising water volume. Experts warned that a sudden outburst could unleash a torrent capable of devastating everything in its path.

Yet, those warnings never translated into action. No robust monitoring system was put in place. No comprehensive risk-mapping was undertaken. No evacuation protocols or red alerts were issued to the villagers who would be in the direct line of danger. Instead, life in Dharali went on, under the illusion of safety – until the glacier proved otherwise.

The Bhagirathi Eco-Sensitive Zone (BESZ) is naturally vulnerable due to its steep terrain, unstable geology, and complex hydrology. But human activity has heightened these risks.

Tourism, unregulated construction, and deforestation have all contributed to destabilising the region. In recent years, there has been a surge in lax construction – settlements along riverbeds and buildings on fragile slopes – without adequate planning or geological assessment. This has obstructed natural water flow, disrupted drainage systems, and increased the likelihood of water run-off, landslides, soil erosion, and floods during heavy rains.

Unchecked tourism, with rapid construction of hotels, roads, and homes, has carved into mountainsides without regard for geological stability. Experts have consistently warned that building in such ecologically sensitive zones without proper safeguards invites landslides, floods, and glacial hazards. Limiting construction on floodplains and enforcing sustainable building practices could have reduced the disaster’s severity. This was not just a failure of foresight; it was a failure of governance. Had the government acted on scientific findings, had there been regulations restricting construction in such sensitive terrain, had there been real investment in early warning systems and local disaster training, more than 900 lives might have been spared. The Himalayan region demands a governance model rooted in precaution, not profit; in resilience, not recklessness.

Human Cost and Impact

Dharali was known for its serene trekking routes, its apple orchards, and its role as a spiritual rest stop. Now, silence fills its streets. Dharali’s economy relies heavily on eco-tourism and pilgrimage. With roads, bridges, hotels, and trekking routes wiped out, visitors have vanished, crippling local businesses from restaurants to homestays.

For many families, tourism was their only livelihood. Now, they face homelessness, loss of income, and deep uncertainty. Recovery will take years, as damaged infrastructure and safety fears keep tourists away. At a relief camp in Someshwar temple, Sushila, who lost her home and everything she owned, quietly cooks for 150 people. “We have no house, no land, no clothes. We are speechless,” she says.

Sushil, a boy from Nepal, searches desperately for his father and six relatives. His last memory is of his father’s call: “Save me, son… I’m drowning in debris,” before the line went dead.

Rescue teams – equipped with sniffer dogs and drones – have saved over 500 people, but many are still missing: locals, migrant workers, and tourists who were in Dharali when the floods hit.

Learning from the Ruins

The government must enforce stringent environmental laws, particularly in sensitive zones like the BESZ. Land-use policies should prioritise natural ecosystem preservation, with all construction projects undergoing rigorous environmental impact assessments.

NDMA guidelines recommend identifying and mapping risky lakes, taking preventive structural measures, and establishing early warning systems. High-risk lakes can be monitored using Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) imagery to detect changes in water bodies, especially during the monsoon season. Measures to reduce lake water volume such as controlled breaching, outlet-control structures, pumping, siphoning, or tunnelling can prevent catastrophic breaches.

Better Disaster Management Systems

Developing advanced early warning systems and community-based disaster preparedness is vital. Local residents should be trained and equipped to respond quickly, since 80% of rescues occur before official forces arrive.

In GLOF or LLOF situations, NDMA advises:

- Installing sirens and mobile alert systems.

- Providing elevated, flood-resistant shelters.

- Stocking rescue equipment – earthmovers, boats, life jackets, portable machinery.

- Deploying Quick Reaction Medical Teams, mobile hospitals, heli-ambulances, and psychological counselling units.

The May 2025 Blatten disaster in Switzerland offers a striking comparison: despite burying 90% of the village, only one life was lost due to early warnings and evacuations carried out days in advance.

Climate Change Adaptation

The government must invest in adaptation strategies – glacial monitoring, improved water management, and resilient infrastructure. Promoting renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and eco-friendly tourism can help protect the Himalayan ecosystem.

“Climate change will manifest as a series of disasters viewed through phones with footage that gets closer and closer to where you live until you’re the one filming it.” – Twitter Source

“The future of the planet depends on the choices we make today.” – Wangari Maathai. The future depends on all our choices and not just the people having authority. Though the government is responsible for formulating policies but it is us who should be taking steps towards better implementation of these policies and environmental conservation.

The Dharali disaster is a grim reminder that in the fragile Himalayas, nature’s warnings cannot be ignored. From Kedarnath to Chamoli to Dharali, the pattern is clear: rapid, unplanned development in eco-sensitive zones is courting catastrophe.

If we continue to carve open mountains for profit, disregard scientific advice, and push nature to its limits, tragedies like this will repeat. The mountains have spoken – now it is our turn to act with respect, restraint, and responsibility.