– Shyama S

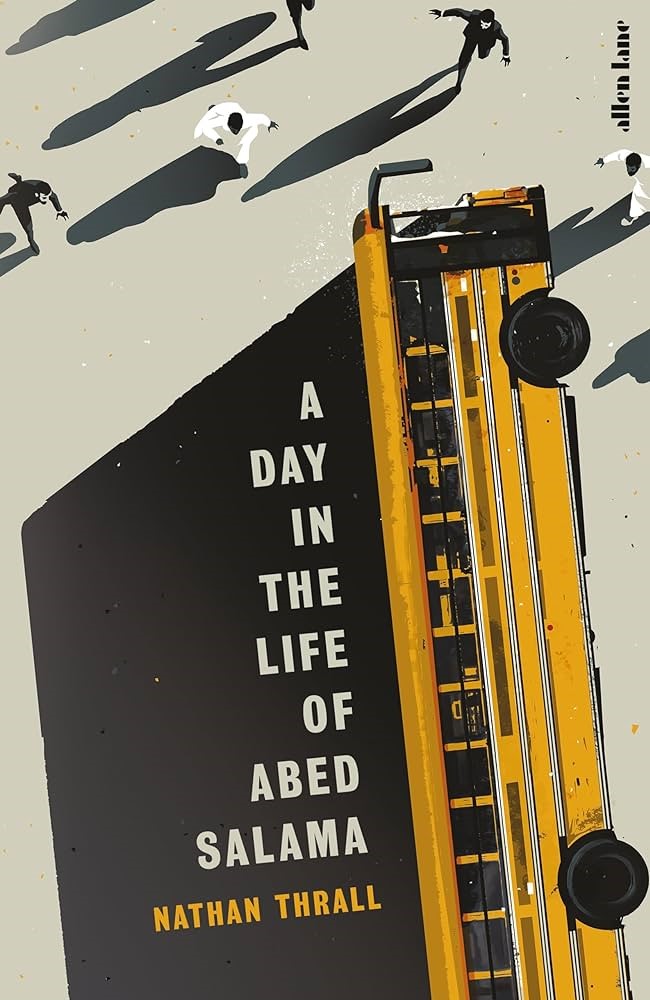

A Day in the Life of Abed Salama: A Palestine Story by Nathan Thrall was released on 3rd October 2023, four days before the unprecedented events of 7th October. As the genocide in Gaza continues unabated, the book has received immense praise for its spectacular granular detailing of the occupation’s physical manifestations – walls, zones, ID cards – that render Palestinians non-citizens in their own land.

A deadly accident outside Jerusalem that took place in 2012 is the focus of the story. A school bus ferrying Palestinian children on a school trip is hit by a truck driven by an Arab Israeli (Palestinian with an Israeli ID) and due to the many restrictions of the occupation, several hours pass before any urgent medical care can be offered to the children caught in the fire caused by the accident. Seven died in it, including children.

Thrall, who lived very close to the site of the accident at that time began to gather information about those affected by it. The narrative unfolds from multiple perspectives – mostly those who were affected by the incident, such as parents of two children, or medical doctors, or even those who were behind the design of the many geographical divisions that separate Palestinians from their own land, making it impossible for them to travel freely.

The children in the school are mostly from the enclosure of what is today around 130,000 people in the town of Anata and the Shu’afat refugee camp. The separation wall restricts them from accessing better facilities of healthcare and schooling in nearby Jerusalem. If their parents sent them to better schools in Jerusalem, they would have to pass through checkposts every day, and instead, they mostly sent their children to schools in West Bank.

One chapter of the book is from the perspective of an IDF colonel Dany Tirza who was the wall’s chief architect. The major principle of the wall was to remove as many Palestinians from the heart of Jerusalem as possible, and lines were deliberately drawn in order to make that happen.

The book argues that the incident, the response to it and the many deaths that took place were all part of a larger structure of occupation. Thrall has faced severe blowback for this book, with about a fourth of the book-related events he had scheduled to be a part of cancelled in the US alone. He was pushed to sign a pledge that he would not advocate for the boycott of Israel, and when he didn’t sign it, his book talk was cancelled.

The physical and legal boundaries that shape the lives of Palestinians living in East Jerusalem have come to life in his book in a way that truly explains how the occupation works on the ground in an everyday sense. Many Palestinians in East Jerusalem like Abed Salama send their children to private schools because the public ones are crowded and drug use is rampant in the UN-run schools.

The drivers who used the road on which the accident happened were mostly Palestinians, as Israeli settlers had been provided with better bypass routes. These Palestinian drivers were constantly stuck in check post-traffic and often overtook smaller vehicles to avoid these bottlenecks. The Israeli ambulances that would not have been stopped at any check post never came to the site on time. What could be read merely as a freak incident is contextualised by Salama in the broader questions of the occupation – what does such segregation and separation do to the real lives of Palestinians?

Thrall, being a Jewish-American journalist and former director of the Arab-Israeli Project at the International Crisis Group shows extraordinary sensitivity and attention to detail in depicting Palestinian life in all its detail – the intimate relations of families, the difficult decisions they make, how borders shape and criss-cross their bonds – and how tragedy strikes them almost everyday due to the occupation.

The town Anata that Thrall describes, almost surrounded by the separation wall is suffocating, and yet, filled with the love and joy of Palestinian existence and his lyrical prose gives us a glimpse of how it would be to live in such conditions.

Thrall’s book, due to its timing has become even more necessary, as he has said in interviews that it is lonely to be a Jewish critic of Israel particularly currently, when he faces censorship in all forms.

Overall, the tight narrative makes it a smooth reading, albeit difficult at points, particularly when one can feel the trauma of the families like that of Abed Salama and his son, Milad. All those interested in the geographical manifestations of occupation must pick it up in order to get a bird’s-eye view of not just one incident, but the structure as a whole.