– Dr. M. Iqbal Siddiqui

Islamic history writing, or tārīkh, emerged in the 7th century as a vital tradition to document the life of Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, the early Muslim community (Ummah), and the spread of Islamic civilisation. Rooted in a religious imperative to preserve truth (sidq), Islamic historiography is distinguished by its commitment to honesty and methodological rigour, balancing narrative storytelling with analytical depth. This dedication to accuracy, driven by Qur’anic injunctions against falsehood (e.g., Surah Al-Baqarah 2:42), contrasts with contemporary distortions of history, such as those in India, where political agendas threaten pluralistic heritage. Islamic historians, from al-Tabari to Ibn Khaldun, saw their work as a sacred duty, ensuring events were recorded with integrity to guide the Ummah and posterity.

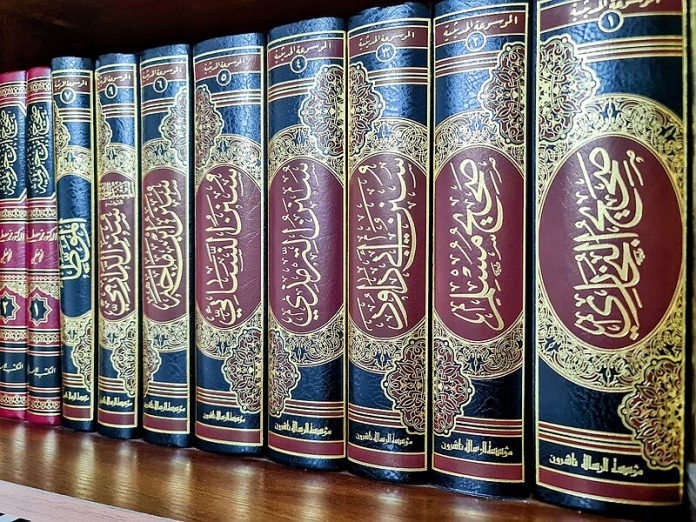

The hallmark of Islamic historiography’s honesty lies in the isnād system, a chain of narrators tracing a report back to an eyewitness, borrowed from hadith scholarship. Historians like al-Bukhari, in his Sahih collection, meticulously verified each narrator’s reliability (thiqa or ثقه), assessing their character and memory to ensure credibility. For example, al-Tabari’s History of the Prophets and Kings (10th century) includes multiple isnād chains for a single event, such as the Battle of Badr, allowing readers to evaluate competing accounts — a practice akin to modern source criticism. This transparency fostered trust in historical narratives.

However, complementing isnād was jarh wa ta’dīl (criticism and validation), a rigorous evaluation of narrators’ trustworthiness. A narrator deemed unreliable (da’īf) due to bias or poor memory was excluded, as seen in Ibn Hisham’s careful curation of the Prophet’s biography (Sīrah). Although later Islamic history writing did not rely on isnād in the same way as early historiography and hadith scholarship did. Later historians, such as those in the Mughal era, incorporated archival records, including court decrees, to enhance empirical accuracy. Abul Fazl’s Akbarnama (16th century), for instance, drew on Mughal administrative documents to chronicle Akbar’s reign with precision. By blending oral traditions, written sources, and critical scrutiny, Islamic historiography established a robust framework for accuracy, offering a lens to critique modern historical manipulations.

Unfortunately, later Islamic historiography, too, fell prey to patronage-driven glorification, but its scholarly tradition of isnād provided a framework for scrutiny that NCERT’s current textbook revisions deliberately sidestep.

Characteristics of Islamic History Writing

Islamic historiography is a vibrant tapestry, blending religious purpose, narrative richness, and intellectual curiosity. Its character emerges vividly through the works of historians who crossed empires and cultures to record the past.

Take Ibn Khaldun, the 14th-century Tunisian thinker, who observed the rugged Bedouin tribes of North Africa. In his Muqaddimah, he pioneered a sociological theory of history, arguing that dynasties rise and fall through the tension between nomadic vitality and urban decadence. This analytical depth, rooted in the belief that history reflects divine patterns, exemplifies the chronological and moral orientation of Islamic historiography. Similarly, al-Tabari’s History of the Prophets and Kings narrates events year by year—from creation to the Abbasids — framing them as part of God’s plan and moral instruction.

The diversity of genres reveals its intellectual breadth. Al-Masʿudi, a 10th-century historian, travelled across the Indian Ocean to Gujarat, marvelling at Hindu temples and Jain merchants. His Meadows of Gold blends universal history with ethnography, drawing on Greek, Persian, and Indian influences. Biographical dictionaries (tabaqāt), such as Ibn Hajar’s works on scholars, preserved the Ummah’s intellectual lineage, while regional chronicles detailed the life of cities like Baghdad or Damascus. Together, they reflect a cosmopolitan curiosity, far wider than many contemporary traditions.

At its core, Islamic historiography combined oral and written sources. Early historians like al-Waqidi relied on reports from the Prophet’s companions, recording them with isnād chains to ensure reliability. Al-Baladhuri’s Conquests of the Lands (Futuh al-Buldan فتوح البلدان) similarly mixed vivid anecdotes with rigorous verification, preserving the memory of Islam’s early expansion.

Leadership and community remained central themes. Works such as Firishta’s Tārīkh-i Firishta (16th century) chronicled Muslim rule in India, celebrating emperors like Akbar while reinforcing the Ummah’s unity. Though often legitimising rulers, these histories still sought to balance political aims with fidelity to truth.

Finally, the multilingual scope of Islamic historiography mirrors the diversity of the Muslim world. Written in Arabic, Persian, Turkish, and Urdu, it embraced cultural pluralism while maintaining an Islamic core. Al-Biruni’s Kitāb al-Hind (11th century), with its meticulous study of Indian traditions, exemplifies this spirit of engagement with other civilisations.

Indian Historiography

Indian historiography, shaped by a pluralistic society, contrasts with Islamic traditions in its diversity and evolving methodologies. Traditionally, works like Kalhana’s Rajatarangini (12th century) or the Puranas wove history into mythology and genealogy, lacking the isnād -driven rigour of tārīkh. Romila Thapar describes these as “embedded” histories, where historical narratives emerge from literary texts, unlike Islamic historiography’s explicit chronological focus.

Recent Indian historiography, influenced by postcolonial and subaltern studies, has embraced inclusivity:

- Subaltern Studies: Ranajit Guha’s work, such as on peasant revolts, centres marginalised voices — peasants, tribals, workers — using oral histories.

- Regional and Cultural Histories: Studies of Bhakti-Sufi syncretism or regional histories (e.g., Kerala) highlight India’s diversity, differing from Islamic historiography’s universal scope.

- Postcolonial and Interdisciplinary Approaches: Partha Chatterjee challenges colonial biases, reinterpreting texts like the Mahabharata as historical sources, unlike Islamic historiography’s reliance on verified narratives.

- Economic and Environmental Focus: Recent works on ancient economies, as noted in IGNOU Corner, use interdisciplinary methods, contrasting with Islamic historiography’s secondary economic focus.

Indian historiography’s pluralism and inclusivity contrast with Islamic historiography’s religious unity and methodological consistency.

Undermining Plural Heritage

Since the BJP assumed power in 2014, revisions to school textbooks by the NCERT have generated debate, with proponents viewing them as a necessary rationalisation and critics seeing them as ideologically driven distortions that marginalise Muslim and secular narratives while promoting Hindutva communalism. Official NCERT documents frame these changes as efforts to reduce academic burden post-COVID-19, as outlined in the 2022 press brief on textbook rationalisation, which states that the exercise aimed to create “rationalised textbooks” for the 2022-23 session by removing overlapping or irrelevant content. Detailed lists of rationalised content for classes 6-12, published on the NCERT website in 2022, specify deletions across subjects, including history. For instance, the Class 10 rationalisation booklet notes the removal of sections on Mughal courts and communal riots to streamline the curriculum.

NCERT officials and BJP supporters defend these revisions as correcting historical imbalances and fostering national pride. BJP leader Kapil Mishra described the changes as “a great decision to remove false history of Mughals,” arguing they eliminate the glorification of invaders. Government-aligned voices, such as those in a 2023 India Today analysis, assert that the revisions address Marxist biases in earlier textbooks, promoting a more balanced portrayal of India’s past. The 2023 National Curriculum Framework for School Education further supports this by emphasising integrated learning from ages 3-18, indirectly justifying content streamlining.

However, academics and Opposition figures contend that these changes selectively omit Muslim contributions and secular elements, aligning with Hindutva ideology. For example, revisions since 2017 have reduced coverage of the Mughal dynasty (1526–1857), downplaying achievements like the Taj Mahal and Akbar’s religious tolerance, as documented in rationalised lists for Classes 11 and 12. Unlike Muslim historiography’s celebration of Mughal legacies in works like Akbarnama, these portray Mughals primarily as foreign invaders. References to Mahatma Gandhi’s opposition to Hindu nationalism and his assassination by Nathuram Godse have been deleted, alongside Nehru’s secular vision, as noted in critiques from the American Historical Association.

The 2002 Gujarat riots, which killed over 1,926 (The Concerned Citizens Tribunal Report) Muslims, have been removed from textbooks, while the 1984 anti-Sikh riots remain, raising questions of selectivity. Historians like Romila Thapar, in a 2023 BBC interview, argued such omissions undermine introspection and promote a monocultural view. Textbooks now glorify Hindu dynasties like the Cholas, often ignoring Muslim interactions, as highlighted in Al Jazeera reports. City re-namings, such as Allahabad to Prayagraj, and campaigns to reclaim Mughal mosques (e.g., Babri Masjid, Gyanvapi Masjid) further erase Muslim heritage. Initiatives like the Varanasi temple corridor prioritise Hindu symbolism, sidelining pluralism.

The Indian History Congress has labelled these revisions “anti-national” for eroding pluralism, with scholars warning of communal polarisation. Unlike Islamic historiography’s isnād -driven accuracy, these revisions prioritise ideology, threatening India’s democratic fabric.

Preserving Pluralism

Islamic history writing, with its isnād system, jarh wa ta’dīl, and narrative richness, exemplifies a commitment to truth, as seen in Ibn Khaldun’s sociological insights and al-Mas’udi’s Indian travels. It contrasts with Indian historiography’s pluralistic evolution, yet both face ideological pressures. Recent revisions in India, rationalised by NCERT as burden reduction but critiqued as Hindutva-driven, undermine the nation’s syncretic heritage.

Historians must resist politicisation to preserve India’s plural past. Preserving plural heritage requires not only resisting politicisation but also fostering historical literacy among citizens, encouraging independent research, and reclaiming India’s shared past from partisan hands.