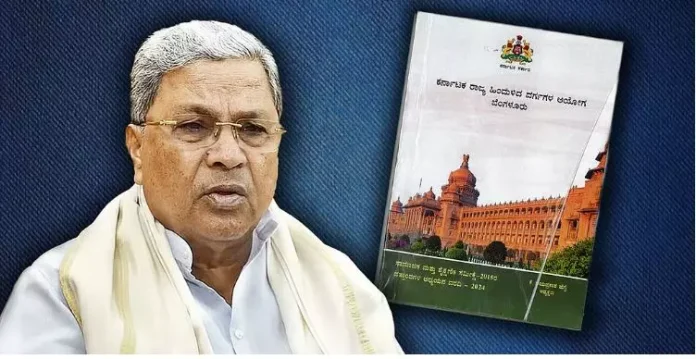

Bengaluru : Leaked excerpts from Karnataka’s long-awaited Social and Educational Survey, originally commissioned by the Siddaramaiah-led Congress government in 2015, have brought to light significant disparities in the socio-economic status of communities across the state. The data reveals that Muslims, despite being one of the largest religious groups, continue to remain in the “More Backward” category, while Brahmins, who make up just 2.62% of the state’s population, are the most socially advanced, reported the NewsMinute.

According to the leaked findings accessed by The News Minute, the survey assigns a composite backwardness score out of 200—100 points for social indicators, 68 for educational, and 32 for livelihood. Communities scoring above 90 are considered “Most Backward,” those between 50 and 89 as “More Backward,” 20–49 as “Backward,” and below 20 as “General” or least backward.

Brahmins emerged with the lowest overall backwardness score at just 11.29, making them the most advanced among the 23 major caste and community groups surveyed. Lingayats and Vokkaligas, two influential communities that have also opposed the survey on various grounds, follow closely with scores of 41.58 and 42.6 respectively, placing them in the “Backward” category.

Muslims, meanwhile, ranked seventh in the list and fall in the “More Backward” bracket, along with communities like Marathas, Tigalas, Ganigas, and Idigas. This categorisation underscores the structural disadvantages that persist in areas such as education, livelihood, and basic amenities.

The survey evaluated social backwardness based on living conditions, type of occupation (especially those seen as ‘unclean’), access to housing and sanitation, type of cooking fuel, and reliance on public lighting and toilets. Educational indicators included school and higher education access, while livelihood was assessed based on employment in the unorganised sector and income levels.

In the realm of education, Bunts and Brahmins were among the least backward, followed by Christians and Jains. When it came to livelihoods, Jains, Lingayat-Veerashaivas, and Vokkaligas showed relatively better outcomes, while Brahmins were also among the top six.

At the bottom of the ladder were the Uppara community (score: 134.88), Bestha (129.45), Kuruba (123.5), Agasa (120.76), and Kumbara (111.09)—all of whom fall in the “Most Backward” category. These communities are primarily engaged in traditional occupations like fishing, shepherding, washing clothes, and pottery.

These latest findings echo the conclusions of the 1990 O Chinnappa Reddy Commission, which found that Brahmins, Lingayats, and Vokkaligas enjoyed disproportionate access to government jobs and higher education. For instance, Brahmins, who constituted just 3.5% of the population in 1988, held 19.5% of the elite Group A and B government jobs. Similarly, their access to higher education (21.5%) far exceeded their demographic share.

The Commission also noted the under-representation of communities such as Muslims, Bedas, Idigas, and Gollas in both education and government employment, a pattern that continues today. Lingayats and Vokkaligas, while not as dominant in government employment as Brahmins, had higher political representation in the state’s legislative and local governance bodies.

Interestingly, the three communities—Brahmins, Vokkaligas, and Lingayats—that have consistently opposed the caste census citing concerns over under-counting, have emerged as among the most socially advanced. Analysts suggest this resistance may stem from fears of losing socio-political dominance if data-driven redistribution of resources takes place.

The leaked data, though incomplete, provides a stark reminder of the entrenched inequalities in Karnataka’s social fabric. It reinforces the need for policies rooted in empirical evidence to address the developmental gaps among marginalised communities, including Muslims—who despite their large population, continue to be left behind in terms of socio-economic progress.