Brahma Prakash’s 2023 book is a critically-acclaimed, yet popular work that has – to paraphrase from its titles – broken the barricades of genre, form and theme in a way that few academic texts have done lately.

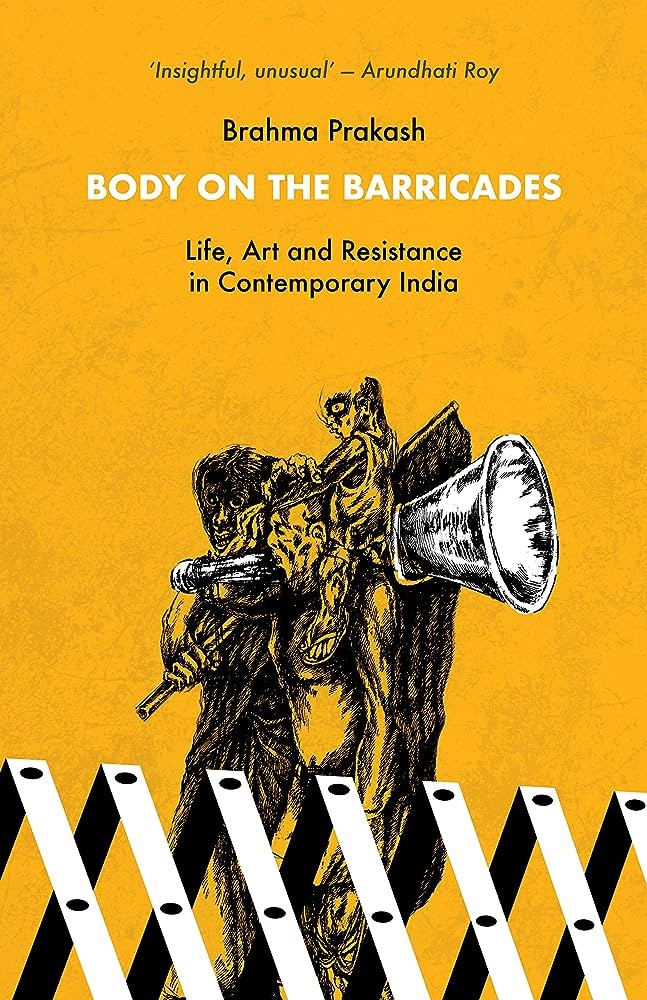

Body on the Barricades: Life, Art and Resistance in Contemporary India

Brahma Prakash

Leftword, 2023; Rs 325, paperback

– Shayma S

– Shayma S

“Before I proceed and you preside, let me clarify that this is not a book on the pandemic…The book is about a pandemic-like situation. The urgency of life and the barricading of freedom. The dilapidated socio-political and health condition…The book is about earnest hope in the face of extreme curtailment…Body on the Barricades is a book of essays on the curtailment of life, art and freedom in contemporary India. It is about a situation that stands at the edge…about thinking about life and freedom from points of confinement…about the situation in which we cannot breathe, but we breathe. As the authoritarian regime pushes its boundaries, curtails our life and freedom, we have no option but to walk.” (p 15-16).

Brahma Prakash’s 2023 book is a critically-acclaimed, yet popular work that has – to paraphrase from its titles – broken the barricades of genre, form and theme in a way that few academic texts have done lately. With a front-cover blurb by the author Arundhati Roy, and half a dozen more on the back cover by more celebrated authors and academics, the book promises right at the outset to be something special, and it is. It does not disappoint, but wants to leave more from the author and perhaps to sit down with him and discuss the current political situation in even greater detail.

The author, who is a professor at the School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University does that rare thing – write a book that is equal parts accessible for the non-academic reader, and yet, does not dilute its sharpness or urgency in order to make it understandable.

Previously, he has written Cultural Labour: Conceptualizing the ‘Folk Performance’ in India (2019). His grasp over the performing arts and its associated theories shines through subtly in a 210-page book that touches on the following topics: the pandemic, demagoguery, Islamophobia (or what he calls Muslim-hating), migrant labourers and their long walk back home during COVID, artists and poets and their role in a time of authoritarianism, recent protests, the Una strike and the idea of death, mourning and solidarity.

Despite the vast swathe of topics, the author does not appear overwhelmed but is firmly in control of the flow of the work, perhaps also because it is evident that he speaks personally and intimately, rather than with a detachment or purely distanced gaze.

On the pandemic and the consequent curtailment, which forms sort of a background or a metaphor that runs through the book, he says poignantly, that while the pandemic brought a new way of life for many – those of us who could work from home while grousing a little about lost freedom – for others, it was a familiar curtailment, a familiar condition of life.

“Before the curtailment reached my home”, he writes, “I didn’t see how others’ lives were curtailed every day.” (p 21).

Curtailment is the book’s major theme – curtailment of the body, of words, of political aspirations, of social freedom. One of the strongest chapters in the book is when he talks about “Muslim-hating”, interspersing his personal experience with it.

His mother, a “lower-caste Hindu woman”, as he describes her, says – “Jo khaay gaay ke gosht, wo na hove Hindu ke dost” – the one who eats beef cannot be believed by Hindus.

An upper-caste Hindu cab driver tells him – “Dil chir bhi de dega toh hum visvas nahi karenge” – We won’t believe them even if they rip apart their hearts for us.

This hatred, lack of trust, and contempt towards Muslims ties together many people, and the idea of the ‘Hindu rashtra’, argues the author.

Since many of the chapters focus on the use of language, another interesting reference he mentions is in the context of the debate between the use of terms like ‘communal violence’ as opposed to ‘pogrom’. He mentions Hasni daiya (sister), Muslim woman vegetable vendor in his village:

“Her image stuck with me. A smiling, frail, low-caste Muslim woman walking with vegetables on the low-caste Hindu streets. She was selling vegetables when the Babri Masjid was razed. She was selling mangoes when the Mumbai riots happened and the city was ripped apart. She was picking red vegetables when Gujarat was burning red in 2002. She was sitting amidst heaps of onions when Delhi was burning in 2020. In fear, in courage, in the cold, in the rain, in the hot summer, she was out with her basket and cart.

The author mentions that in his area of Bihar, riots were not called ‘danga’, but miyamari. “We don’t try to hide it. We keep it simple… Miyamari (the massacre of Muslims).” We, as children and teenagers, would crack communal jokes on Hasni daiya: ‘You reduce the price or pay the price, miyamari ho jayega (massacre of Muslims will happen…. It did not occur to us how these communal jokes might have hurt her sentiment. Genocidal jokes were part of our jokes; fundamentalism was fundamental to our fun.” (pp. 75-76)

Movements – strikes, protests, marches back home – also form the core of the text. As curtailment increases, so do these movements and shifts. The author sensitively traces the dilemmas of migrants, who leave villages and go to cities for work, and in the pandemic, were forced to march back ‘home’ – when the idea of home itself had changed.

The Una strike of 2016 when Dalits refused to clean up the carcasses and waste after seven members of a Dalit family were flogged for skinning a cow carcass forms another pivotal chapter in the book. The Dalits protested and refused to clean and dispose of the carcasses – “the cities started witnessing horrible scenes. The fouled air was filling the public sphere.” (p. 178)

This brings to mind the recent incident when Muslim houses were demolished in Gurgaon and Muslim workers left the city in fear, the elite residents of the high-rise towers were alarmed because the garbage was accumulating, their houses were in shambles and there was no one to clean the streets.

As Professor K Satyanarayana writes in his blurb of the book, it is a “searing cultural critique of the contemporary nation-body.”

All that is hidden, obscured by the shining veneers of neoliberal growth, ‘smart cities’, and the citizens behind the green tarpaulins that hide the slums of cities – all is revealed in the sharp prose that nevertheless, does not lose its sense of empathy.