The symbolism of Palestinian resistance flows throughout the book. Events, incidents, images, Israel’s unspeakable violations, and the martyrdom of many young men and women – all make the book a compelling read, deservedly demanding one’s patience, commitment and full attention.

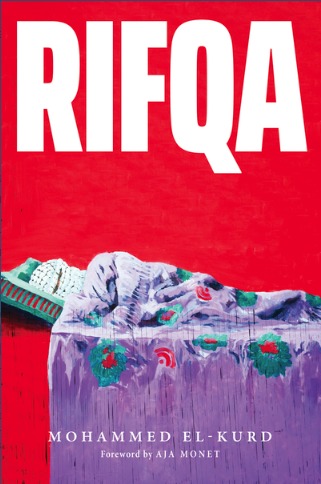

Rifqa

Mohammed el-Kurd

Haymarket Books: Chicago, Illinois

2021

Reviewed by Shyma S.

Reviewed by Shyma S.

Rifqa el-Kurd became well-known to the wider world when Israeli settlers took over her home in 2009 – after several battles in colonial committees in Sheikh Jarrah, the house divided by drywall, and the settlers lived in half the house, frequently attacking the family. In the book, she is irrevocably associated with the imagery of jasmine flowers – as el-Kurd wrote in an obituary in The Nation – “Each day after school my grandmother would welcome me at the door with jasmines wrapped in Kleenex.”

She died at the age of 103 in 2020, living through the Nakba, the 1967 Nakba and passed away during the hubbub over the so-called “Deal of the Century” and the imminent plans of Israeli powers to annex the West Bank. She was older than Israel and lived a life of dignity and self-worth, of survival and resistance. “A soldier as old as a leaf born yesterday/pulls a trigger on a woman older than his heritage,” writes el-Kurd in “Bulldozers Undoing God.”

When the media and solidarity activists began to throng their house which had been occupied by settlers, she refused to merely be a victim or put her life on show as a humanitarian cause. Instead, she would ask the visitors if they were American, and if she received an affirmative answer, would always tell them that America was largely to blame for their situation. She would similarly deal with English visitors. In the last year of her life when she was suffering from dementia and often did not know where she was, she remembered the Nakba in granular detail and how she and her children were subsequently rendered a refugee. El-Kurd too, does not demand any pity or sympathy, only justice.

Rifqa is not an easy book of poems. Readers are advised to stop, pause, and read up on the references. There are many, explicit and implicit. The symbolism of Palestinian resistance flows throughout the book. Events, incidents, images, Israel’s unspeakable violations, and the martyrdom of many young men and women – all make the book a compelling read, deservedly demanding one’s patience, commitment and full attention.

A single poem is enough to occupy one’s mind and time – especially the ones that detail the titular Rifqa el-Kurd’s life. Some lines or phrases will invariably stop the reader and make them catch their breath, especially in the current atmosphere where death and destruction at the hands of the Zionist regime are writ large all over our screens. While Rifqa did not live to see a free Palestine, one of the author’s major regrets, he nevertheless ends the book with optimism for a liberated future.

Ghassan Kanafani, Umm Kulthoom, Nizar Qabbani, Malcolm X, Sinan Antoon, Audre Lorde – their quotes are scattered across the work and connect the Palestinian struggle to a global one as well as the older Palestinian heritage of literary resistance. Some poems contain Arabic phrases or verses from the Qur’an and translations are provided.

A significant contribution of the book is to undercut the “womenandchildren” discourse that has always pervaded zones of oppression and resistance like Palestine.

“womenandchildren” refers to an exceptionalisation or humanization only of women and children in areas of conflict or war where the two (interrelated) groups are seen as innocent and in deserving of aid, rescue or a humanitarian gaze, while men are invariably seen as less deserving of empathy or are seen as perpetrators.

In his afterword, el-Kurd critiques this particular phenomenon and points towards the complexity of the many women characters who populate his book as having complexity and not being papered over in an abstract discourse of innocence. They have agency and are allowed to exist in different shades of the human personality. The term, originally coined by Cynthia Enloe in 1990, can be seen playing out in the current Zionist offensive as well, where Palestinian men are depicted in the media as inherently violent or not in need of rescue or relief. This is visualized in how anger too becomes a luxury – how his father tells him: “Anger is a luxury we cannot afford.”/Be composed, calm, still – laugh when they ask you,/smile when they talk, answer them,/educate them.” The childish rebelliousness of Palestinian children has to be controlled and tamed as they grow up for fear of fatal retribution is traced as well (“Autobiography” – “I was once bold/tire slashing/security camera snatching”)

God and religion are a complicated presence in el-Kurd’s book. The deeply religious Rifqa prays to her “refuged God.” For the Palestinian boys who were killed by Israelis while playing soccer on a beach in Gaza City in 2014 – “What do you say to children for whom the Red Sea doesn’t part?” (“No Moses in Siege”).

The figs and the olives make their appearance (“Born on Nakba Day”). How the Zionists claim divine guarantee of their so-called promised land also makes a mention – “the chosen and the promised/as if God is a real-estate agent.” Prayer and belief are a constant thread through the book, especially through its women characters – his mother and grandmother.

The heart of the book is the poem titled simply, “Rifqa.” Perhaps the longest one in the book – the lines when Rifqa imagines going to her house in Haifa she was forced to leave during the Nakba to say – “Let’s say it was devoured by the sea./ Don’t worry it will wash ashore./”No matter how deep it drowns,/the truth always washes ashore.”