This book provides a concise summary of the various struggles faced by the Muslim community in the last nine years since the ruling party came to power.

Book Review

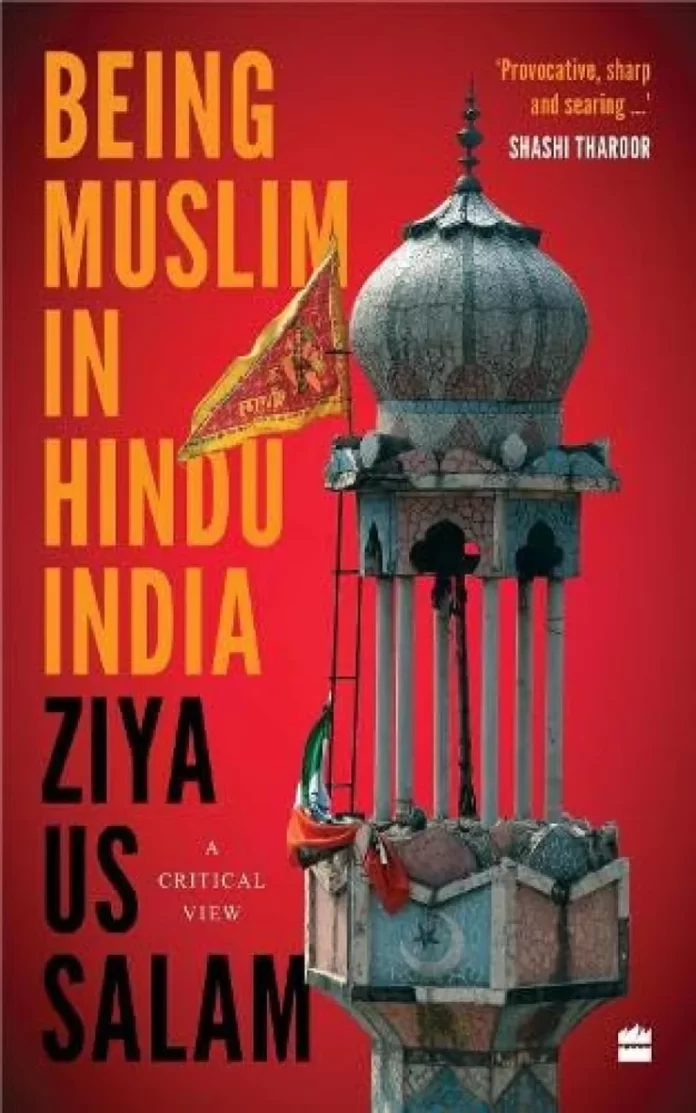

Title: Being Muslim in Hindu India: A Critical View

Author: Ziya us Salam

Publisher: HarperCollins India

Published: 2023

Price: Rs.490 (Paperback)

Reviewed by Firasha Shaikh

From the author of other such pertinent works like Saffron Flags and Skullcaps, Lynch Files and Shaheen Bagh: From a Protest to a Movement, comes another timely book, Being Muslim in Hindu India: A Critical View.

This book provides a concise summary of the various struggles faced by the Muslim community in the last nine years since the ruling party came to power. It takes the reader through the different ways in which Hindu nationalism, virulent and violent, has sought to undermine and destroy the secular fabric of the country by vilifying its largest minority community, Indian Muslims.

Combining the precise, fact-based approach of a journalist with the emotive narrative flow of a storyteller, the focus of the book is to highlight the various methods of marginalization and exclusion of Indian Muslims adopted by the ruling party and the Hindu nationalist movement. The anti-Muslim violence perpetrated by them is not simply limited to physically violent attacks on individuals, but it takes many forms, many of which amount to socio-economic apartheid and, even more alarmingly, are part of a protracted process of genocide.

In Chapter 13, the book mentions “Article II of the United Nations’ Genocide Convention,” which includes in its definition of genocide any act that intends to destroy a religious group completely or partially or inflicts on it ‘conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part.’

From this definition, the genocidal process against Indian Muslims is seen as a multi-front endeavour: political, cultural, religious, social, economic, and psychological.

Part I focuses on “Political Marginalization”. There are certain systemic practices which marginalize and exclude Indian Muslims from being a part and parcel of the nation-building process. The first is the under-representation of Muslims in elected positions such as that of MPs and MLAs. The more insidious one is that of gerrymandering/ reconstituting constituencies (which is the practice of delimiting Parliamentary constituencies in such a way that Muslim-majority constituencies are carved up to split the numerical proportion of Muslims and to make such areas reserved for SCs and/or ST members.) It’s argued that there is a concerted effort to “scatter” or “ghettoize” the Muslim vote. In the same vein, missing names from electoral rolls, prevent Muslim voters from exercising their right to vote or casting their ballot, thus negatively impacting Muslim participation in national politics.

The book’s opening salvo itself, “To be a Muslim is to be an orphan” poignantly indicates one of the major themes of the book, which is the disheartening reality that Indian Muslims lack a true, meaningful ally from the majority community. The Opposition parties also refuse to field Muslim candidates and peddle “soft Hindutva”. Passers-by are silent spectators to violent anti-Muslim hate crimes taking place in front of their own eyes, making no effort to stop them. The majority community repeatedly votes for the party that is hurting their fellow compatriots. Repeated hate speeches and calls for genocide against Indian Muslims by fanatic Hindu nationalists do not evoke even basic condemnation by much of civil society. But the tragedy is that most of civil society has stopped viewing Indian Muslims as fellow compatriots but as an “Other”, a perpetual enemy, in fact, an enemy since many centuries.

Part II discusses the “rubbishing of medieval history”, involving historical erasure, deletion of Mughal and Sultanate history from textbooks, and the renaming of roads, cities, and monuments. A misplaced grievance for supposed historical wrongs of the past is sought to be exacted from the Indian Muslims of today. The author debunks common Hindutva tropes regarding history by citing the works and analyses of seasoned historians and scholars.

Parts III, IV, and V cover persecution based on religious practices and religio-cultural markers, as well as socio-economic marginalisation.

This includes persecution for religio-cultural markers and practices such as hijab bans in schools, being targeted merely from their appearance (skullcaps, beards), persecution for offering namaz (prayer) in public or within homes and sounding the azan (call to prayer) from mosques. The author quotes sociologist Imtiaz Ahmed’s view that these attacks are part of the Hindutva project to annihilate Muslims culturally since physical extermination is not possible. The end game is to “intimidate the community and scare it into silence”. Chapter 17, which covers the attacks on mosques especially during the 2020 Delhi riots is powerfully written and deeply poignant.

The author goes on to enlist attempts at socio-economic marginalization including attacks on businesses during pogroms/riots, bans on livelihoods such as cattle trade and slaughter, and prohibitions on selling halal meat, especially during Hindu festival times (food fascism), etc. The author minces no words in clearly identifying what all of the above constitutes; “socio-economic apartheid” of Indian Muslims.

Part 6 focuses on the sheer extent of dehumanization, which makes such apartheid and persecution possible. The relentless propaganda spread by Hindu nationalist politicians, Islamophobic media channels and fake news on social media; all contribute to the dehumanization of Indian Muslims. Such that even police and judicial authorities which are supposed to be non-biased and impartial, are not immune. The police stand idly by as Hindu nationalist mobs perpetrate destruction on Muslim houses and businesses. The Supreme Court of India shocked everyone when it chose to let the criminals responsible for Babri Masjid’s demolition walk scot-free.

The COVID-19 global pandemic was a classic case study of these double standards where members of the Tablighi Jamaat were penalized and imprisoned (for holding a meeting well before the lockdown was officially enforced) whilst the Kumbh Mela event, a year later, was not only allowed to happen but justified and encouraged with the blessing of official authorities; even as Covid-19 cases continued to soar in the country.

Part 7, “Finding their Voice” delves into the response and resistance from the Indian Muslim community. Indian Muslims have responded to this crisis in various ways. The affluent section of Muslims has increasingly been moving abroad in search of better opportunities and a life without constant fear. Others have resisted the attempts at marginalization by excelling in the education field. Despite the Islamophobic assumptions spread by the media, the last few years have seen a remarkable growth in Muslim representation in the all-India civil services. When the discriminatory CAA was passed, Muslim women led the way for the rest of the community via the iconic Shaheen Bagh protests throughout the country. These protests were a turning point, in the sense that, for the first time, Muslims saw through the pacifist tactics of certain religious leaders to quell their democratic right to protest and defied them.

The book ends on a sombre yet heartening note, “The night is still not over.” “Yet,” the author writes, “the tiniest ray of light seems to be coming through. It is early but a new dawn may just beckon.”

Analysis

The book throws up several themes that need to be discussed urgently in light of the upcoming Lok Sabha Elections, just a few months away.

First, the need for the majority community to do some serious self-reflection and question the motives for their hatred. They must deprogram themselves from the constant anti-Muslim bigotry being fed to them by the media and their leaders.

Secondly, the Indian Muslim community needs to formalize a list of demands which include repealing discriminatory laws like UAPA, CAA, sedition, etc., for the state to provide due compensation for damaged properties and lives lost during pogroms/riots, to penalize news channels and any politician or leader who spreads fake news or hate speeches, among other important demands. In the case of the latter, there must be a law acknowledging hate speech/hate crimes, which is currently missing in India.

These are however short-term demands. The problem of anti-Muslim hatred is something that is not limited to the emergence of Hindu nationalism by any means; rather it is something which is deeply embedded at a larger structural level as well as among Indian society at large. Uprooting this hatred and dehumanization cannot be limited to any one aspect; there will need to be a paradigmatic change at all levels; from the very state apparatus down to the basic level of society.

Critiques

For all its notable aspects, a significant shortcoming of the book is that the reasons behind this anti-Muslim hatred are not explored. Readers might have benefitted more, had the deeper psycho-social motives and driving factors behind these anti-Muslim actions been examined in greater detail. How was it possible for such levels of animosity to take root in the Hindu society? Why is there so much apathy among the majority community; why don’t more Hindu folk speak out against anti-Muslim hatred? And most importantly perhaps, how has Islamophobia become the mainstay/the backbone of Indian politics?

In the history section, the author clarifies some oft-repeated myths, but mentions jizya as being “a discriminatory tax”. This is problematic since jizya was not discriminatory, rather it was a tax which non-Muslim subjects paid to the Muslim ruler for their protection. Failing to clarify this may reiterate the misconception about jizya which prompts so much of the misunderstanding of medieval history.

Apart from these missteps, this book is a deeply compelling summarization of what the Indian Muslim community has been facing for the past decade.

Given the brevity of public memory and larger Indian society’s propensity towards being influenced by propaganda, this book is a timely reminder before the upcoming National Elections.

It also serves its purpose as being part of the larger attempts by the community at documentation of these events, for posterity.