– Mohammed Atherulla Shariff

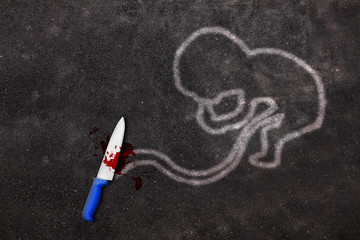

Bengaluru, Dec. 14: Over 900 illegal abortions have been reportedly conducted in three years at one medical centre in Mandya, the sugar town of Karnataka. Recent raids in Mandya and Mysuru exposed a prenatal sex-determination and female foeticide racket operating in the dark.

The network that has been busted in Mandya is just a tip of the iceberg, there is a suspicion that many more are still operating, says Janardhan. He works with Vimochana – one of the few organisations that have continued to work against sex-selective abortions in the state.

Karnataka is one of the nine states that have seen a significant decline in sex ratio at birth between 2016 and 2020. And it has the second lowest sex ratio in South India, after Telangana. The grave reality is that thousands of girls continue to be killed in the womb even today.

“There are several well-established networks of doctors, quacks and agents who drive gender-biased abortions,” says Dr Sanjeev Kulkarni, a gynaecologist and pioneer in the fight against sex-selective abortion in India.

The brutal practice that denies a girl the right to be born is driven by many factors – patriarchy, preference for sons, concerns about dowry, low social and economic status accorded to women, the disappearance of traditional roles in agriculture and the poor implementation of law. One recent addition, parents say, is fear around women’s safety.

Violence, social ostracisation, lack of financial support and sustained pressure – these are only some of the most common consequences women face for ‘not bearing a male heir’.

Is women’s education a bane?

With better education and awareness, women are also demanding their rightful share in ancestral property, which has put patriarchal families in a tough spot, says Varsha Deshpande, an advocate and activist striving for the implementation of the Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques Act, 1994 (PC-PNDT Act) in the country. “This is also resulting in female foeticide in affluent families,” she says.

Varsha, who is a member of the National Inspection and Monitoring Committee under the Act, blames the government for a failure to implement adequate measures to stop discrimination against girls even prior to their birth.

The lackadaisical attitude could also be because, “there is a lack of urgency now since most people have come to believe that the problem is solved,” says Ravinder Kaur, a professor at the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi. Kaur has been involved in extensive work on gender-biased abortions in the country.

Societal behaviour, ineffective system and greed

A major hurdle in registering and processing complaints has been finding evidence in cases of illegal abortions. The racket of sex determination and abortions usually operates in far-off villages, districts or even states. In such scenarios, locals are not able to point out even when or where the crime was committed

These elusive, well-networked criminals have flourished, taking advantage of society’s patriarchal mindset and the administration’s indifference. That only 100 cases have been filed in the state under the PC-PNDT Act since 2002 shows the lack of strict action on the part of the departments concerned. The accused have been convicted under the Act only in 15 instances.

“It becomes impossible to file a case as there is immense pressure from various quarters. It would help if there is a provision for teams from other districts or the state team to take action based on the intelligence provided by the home district team,” the activists say.

Officials from the health department say that a major drawback under the PC-PNDT Act is that there is little provision for the health department and the police to collaborate.

Inordinate delay in disposing of cases adds to the problem. “Four judges have changed since I filed a case in 2014. Ironically, from the police to the lawyer, they come to me seeking more details about the provisions of the Act and the case,” says Janardhan, an activist who has been fighting against sex-selective abortion in Mandya and Ramanagara districts for the last two decades.

While state and district-level committees have been set up to monitor, inspect and take action, many members or former members point to the laxity on the part of the administration in planning and executing mandatory activities. The low level of awareness among committee members about the provisions of the Act makes these committees ineffective.

Communities Differences

Female foeticides are alarmingly huge among Hindus and Sikhs – more than their population ratio and are lowest among Muslims.

A Pew Research Center research based on Union government data indicates foeticide of at least 9 million females during 2000-2019. The research found that 86.7% of these foeticides were by Hindus (80% of the population), followed by Sikhs (1.7% of the population) with 4.9%, and Muslims (14% of the population) with 6.6%.

Similarly, child sex ratio greater than 115 boys per 100 girls is found in regions where the predominant majority is Hindu; furthermore “normal” child sex ratio of 104 to 106 boys per 100 girls are found in regions where the predominant majority is Muslim, Sikh or Christian. The Indian government has passed PCPNDT in 1994 to ban and punish prenatal sex-screening and female foeticide. It is currently illegal in India to determine or disclose sex of the foetus to anyone. However, there are concerns that PCPNDT Act has been poorly enforced by authorities.

Adverse effects of technology

Female foeticide has been linked to the arrival, in the early 1990s, of affordable ultrasound technology and its widespread adoption in India. Ultrasound technology arrived in China and India in 1979, but its expansion was slower in India. Ultrasound sex discernment technologies were first introduced in major cities of India in 1980s, its use expanded in India’s urban regions in 1990s, and became widespread in 2000s.

The consequences

The consequences of sex-selective abortions are profound. Not only are these practices in violation of basic rights of girl children, but they also change the composition of a population.

Today, despite policy measures such as Beti Padhao, Beti Bachao and Bhagyalakshmi, people still consider girl children as liabilities. Dr. Kulkarni says, “It is time we take the problem seriously and launch awareness campaigns.” He stresses that educational and religious institutions, which have a huge hold over the population, take the issue up and work towards solving the problem.

Government to gear up

The state government will formulate a new policy to curb female foeticide and improve gender ratio, Karnataka Health and Family Welfare Minister Dinesh Gundu Rao said. The government will also establish district-level Pre-Conception and Pre-Natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT Act) cells across the state and set up a state-level task force to curb foeticide, he said.

Rao said the state needed to make laws more stringent to curb foeticide. He lamented that the gender ratio in the state was dropping, while stressing the need for more social awareness. “Tracking these incidents is a challenge as they are done in through oral medication, without any surgical procedure. In many cases, those involved are not even certified doctors,” he said.