– Radiance News Service

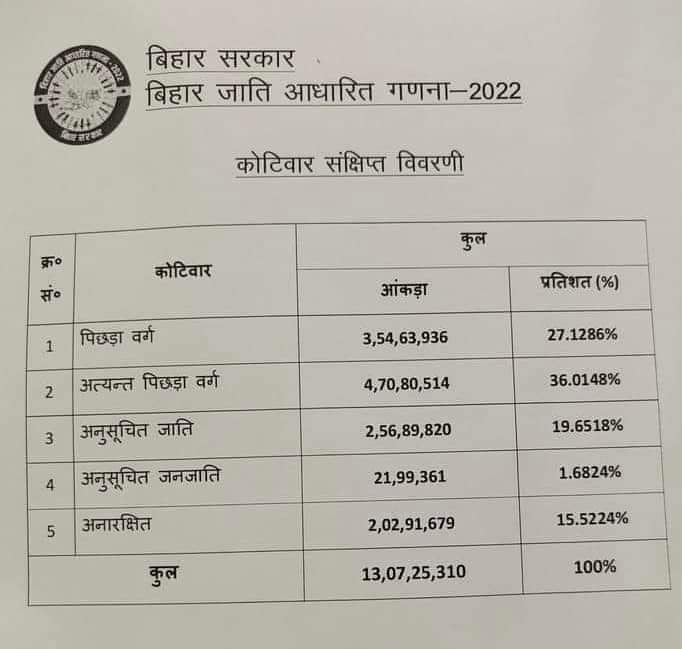

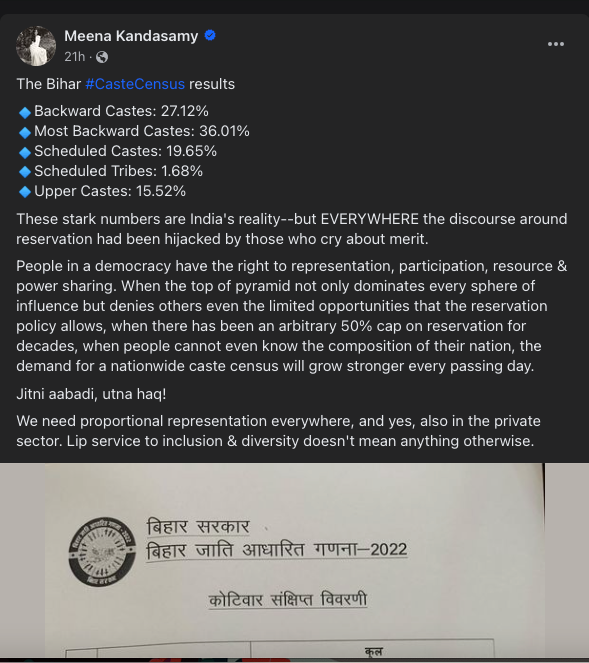

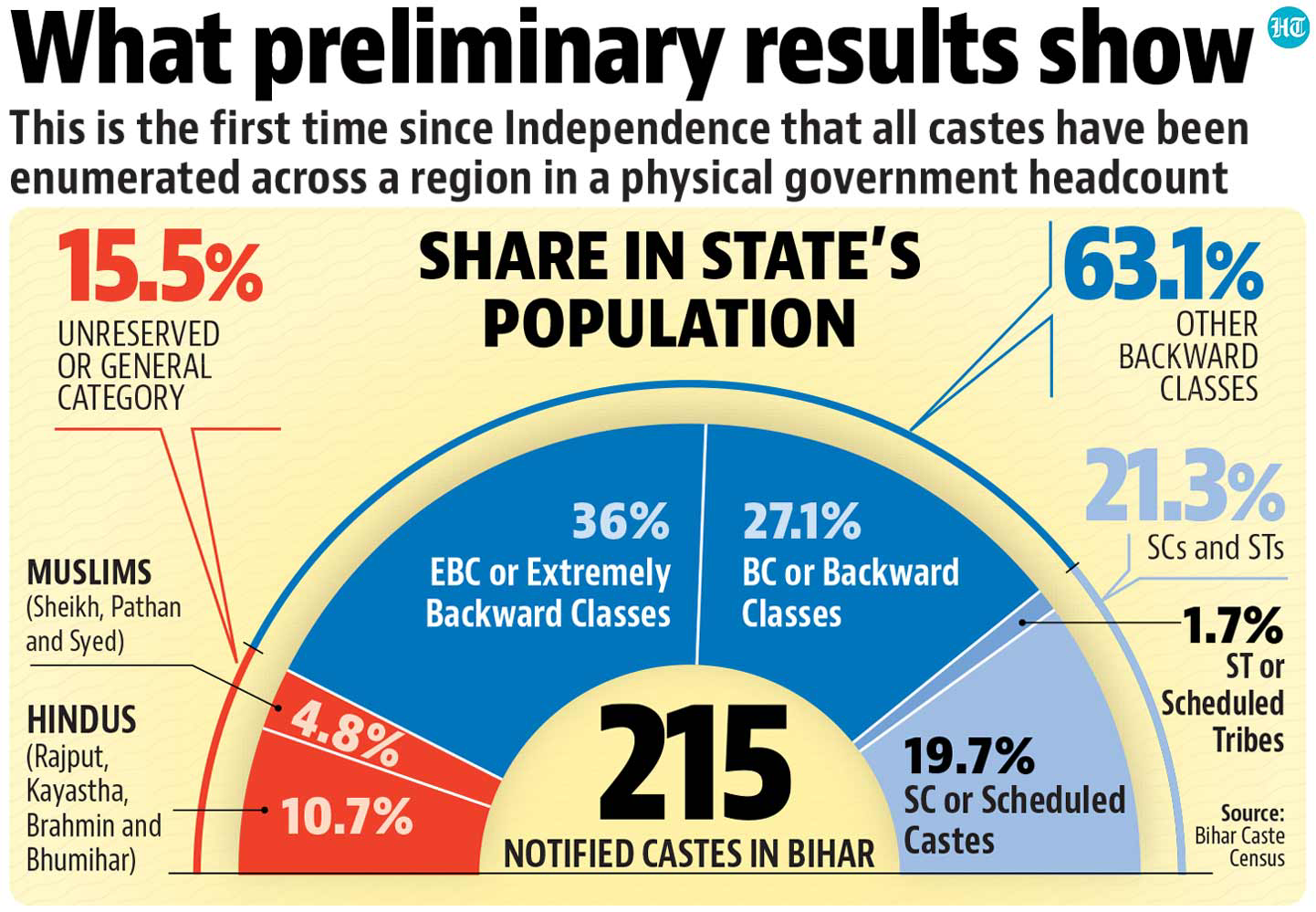

New Delhi, 4 October 2023: In Indian politics, it has been a busy time with respect to the representation question. First, the panel headed by former Justice Rohini of the Delhi High Court submitted the Commission’s report – after 14 extensions – on the sub-categorisation of OBC groups. Now, with the results of the Caste-Based Survey Report – the caste census or the ‘headcount’ as the CM and Dy CM of Bihar are calling it due to a legal tussle, the demographics of the state points towards a clear “85-15” cleaving. With only 15% of the so-called upper castes making up the population while the backward castes, extremely backward castes, SCs and STs make up the rest, the results have thrown up interesting, if unsurprising results for those who watch Bihar society closely. OBCs and EBCs make up 63% of Bihar society, while Muslims (putting together those within these categories and unreserved) are at 17.708%.

In Uttar Pradesh, Kanshi Ram had given the slogan “Jiski Jitni Sankhya Bhari, Uski Utni Hissedari” which had become a rallying cry for the movement for social justice and political representation. Now, it is “Jitni Abadi, Utna Haq” that has been taken up as a slogan by the Congress, which has otherwise not expressed great enthusiasm for a caste census in the past.

In February 2023, during its 85th plenary session in Raipur, the All India Congress Committee adopted a resolution supporting reservations for the Scheduled Castes and Tribes and OBCs in the higher judiciary and the private sector. Mallikarjun Kharge, the dynamic, Buddhist-Ambedkarite president of the Congress who has completed one year of his leadership, too has been pushing for it.

Every Census in independent India from 1951 to 2011 has enumerated data on SCs and STs, but not the overall picture, leaving the true dimensions of the vast amount of OBC groups unclear and fuzzy. Therefore, the last all-India data on caste in its most comprehensive form remains the 1931 Census, which included modern-day Pakistan and Bangladesh. The Mandal Commission estimated the OBC population at 52%. With an approved budget of Rs 4,893.60 crore, the 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC), 2011 was conducted, but while the economic data was finalized and released to the public, the caste data remains under wraps even today.

The caste census is not merely an administrative exercise that renders populations legible and governable for states, but also has significant political, social and economic implications. As political science researcher, Thallapelli Praveen wrote in Outlook in 2021: “The aim of a caste census is not to know the numerical strength of a caste. Rather, it would reveal social inequalities for possible remedial measures.” While the economic data of the survey is yet to appear, the demographic data has generated a buzz of its own. Opposition parties in recent times have been increasingly demanding an all-India caste census, linked to the pending and long-delayed national Census. With the announcement of the Bihar census data, the debate has been revitalized.

Visibly irked by the caste census and its possible fallout, PM Modi seemed to insinuate at a public rally that the politics of caste division was being employed by the opposition. However, if the society in question has a clear and existing caste division – a division of labourers, not just a division of labour as Dr BR Ambedkar had characterized Indian society – then it is the responsibility of the state to first correctly identify and numerate the existing divisions in order to offer solutions. In short, a correct diagnosis must precede treatment.

Indian economist Jean Dreze wrote in 2020, “Of all the ways upper-caste privilege has been challenged in recent decades, perhaps none is more acutely resented by the upper castes than the system of reservation in education and public employment.” With time, it has become difficult for major political parties and social organisations to outrightly oppose reservation, with even the RSS supremo recently saying that “people should be willing to suffer for 200 years as retribution.”

Apart from the caste arithmetic, the survey also provided religion-wise data – Hindus at 81.99 per cent (10.71 crore) followed by Muslims, 17.7 per cent (2.31 crore), Buddhists, 0.08 per cent (1.11 lakh), Christians, 75,238 (0.05 per cent). Sikhs, 14,753 (0.01 per cent) and Jains at 12,523 (0.009 per cent). There were 1.66 lakh people who followed other religions while only 2,146 said they did not follow any religion.

The Muslims who comprise 17.708% of the state are vastly underrepresented in the state legislature, even if the representation far outstrips many other states – out of 243 total members, Muslims are at 7.82%. The caste census results may provide a shot in the arm for Muslims to demand greater representation. Some sub-groups have seen their numbers increase among Muslims.

Another major result of the census is that it puts paid to any argument by the ruling party – who have been relentlessly trying to argue that Muslims should not be entitled to reservation, first in Karnataka, then Telangana – that Muslims are unduly benefitting from reservation or taking advantage of it.

Overall, roughly three-fourths of Muslims in Bihar come under OBC or EBC category while around one-fourth come under the unreserved category. Only 4.8% of Bihar’s Muslims fall outside the OBC-EBC category, and commentators have also raised eyebrows at whether some of these numbers – such as the Shaikh community being pegged at 3% – accurately represent the actual nature of Muslim castes, due to the fact that many such ‘titles’ or caste names are also used by oppressed caste members.

As an academic from Lucknow who wished to be unnamed said, “The exercise must be treated as a role model for the national Census. The reason to assign such a governance exercise as a ‘model’ is because, for the first time, any Census in post-Independent India has captured the castes and their number within the Muslim community and leaves no scope for denial. Of the total Muslims, 3.83 % are Sheikhs (Ashraf caste), followed by Ansaris (3.54 %), Surjapuri (1.87 %) and Dhuniyas or Mansooris (1.42%). The number vindicates the arguments and demands of ‘Pasmanda’ organisations for better representation and resource distribution. Muslim castes listed under EBCs also reflect their economic backwardness and marginalisation. This shall help formulate and allocate needed space for affirmative action toward the targeted most backward Muslim castes.”

On the other hand, 15% of general, unreserved upper castes are also entitled to EWS reservation of 10%, which entirely violates the principles upon which reservation or affirmative action is based, that is, historical exclusion leading to current deprivation, not class. It is to be remembered that the recent Supreme Court judgement upholding the EWS reservation breached the long-cemented 50% quota limit earlier set by the apex court, effectively opening a pathway for the cap to be challenged entirely, perhaps more in tone with the actual population percentages of OBCs.

If properly utilized and understood, the results of the caste census can open the doors to expanding the social justice plank beyond the four major existing communities that have shaped its fortunes and benefited from it in Bihar – Yadavs, Kurmis, Vaishya, and Kushwaha. As Patna-based senior journalist, Chandan told The Wire: “The caste census can throw up complex data, and if properly implemented the Mandal parties may attract new support among different OBC and Dalit communities but may also face the risk of losing their core support base.”

According to a report in The Caravan by Ravikant Kisana, even the Rohini Commission’s initial findings have shown that from “over five thousand OBC communities, only forty or so castes – less than one percent of all OBCs – had managed to secure around half of all the reservation benefits for OBCs in central educational institutions and public services.”

The Sachar Committee Report (SCR) also pointed to this discrepancy, arguing that “Muslim groups namely, gadheris, gorkuns, mehtars or halalkhors, Muslim dhobis, bakhos, nats, pamarias, lalbegis and others remain impoverished and marginalized. Their inclusion in the OBC list has failed to make any impact as they are clubbed with the more advanced middle castes.”

However, because the SCR relied on NSSO data to substantiate the numbers of Muslim OBCs, many raised questions over its reliability, with Ali Anwar Ansari in Masawat ki Jung arguing that OBCs could account for 80% of the Muslim population. A major strand of the debate on reservation among Muslims is whether the entire community should be eligible for reservation, or only the deprived sections.

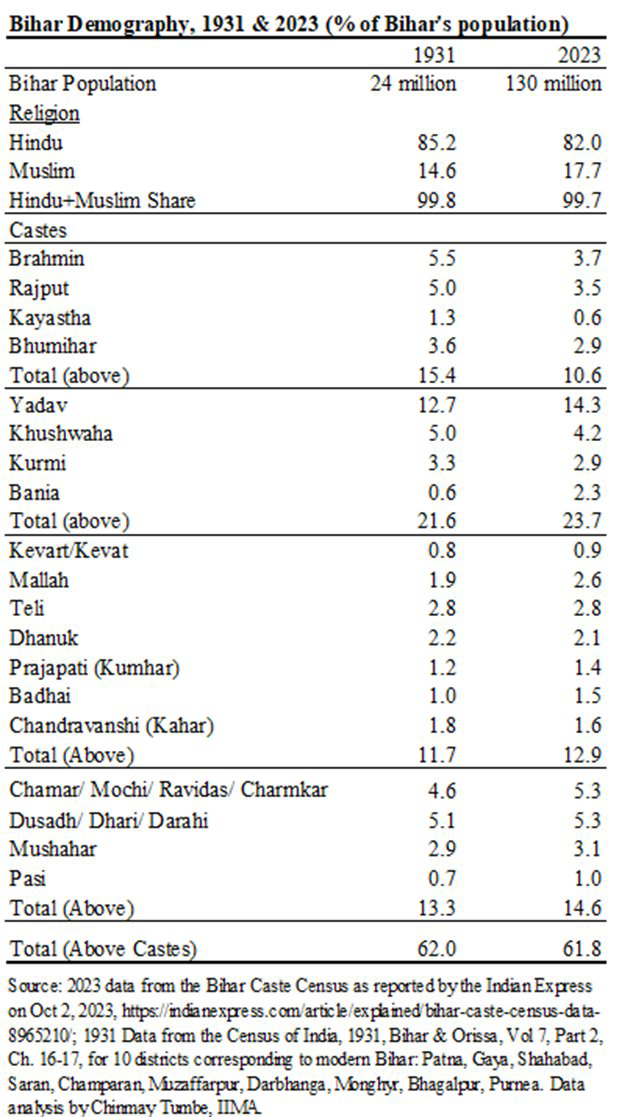

In the above table prepared by Chinmay Tumbe, faculty at IIM Ahmedabad, based on the two Census data sets, it is revealed that the Muslim population in Bihar has grown – but not substantially – from the 1931 Census to the present from 14.6% to the current 17.7%. This is due to a fertility differential that has slowed down in the rest of India, but less so in Bihar among Muslims, and more importantly, due to the phenomenon of selective migration out of Bihar, where it is mostly the upper castes and social elites who have left Bihar. Muslims are seen as less likely to leave Bihar than their Hindu counterparts. Overall, the Census of Bihar reveals broad stability of population among caste and religion shares.

In the above table prepared by Chinmay Tumbe, faculty at IIM Ahmedabad, based on the two Census data sets, it is revealed that the Muslim population in Bihar has grown – but not substantially – from the 1931 Census to the present from 14.6% to the current 17.7%. This is due to a fertility differential that has slowed down in the rest of India, but less so in Bihar among Muslims, and more importantly, due to the phenomenon of selective migration out of Bihar, where it is mostly the upper castes and social elites who have left Bihar. Muslims are seen as less likely to leave Bihar than their Hindu counterparts. Overall, the Census of Bihar reveals broad stability of population among caste and religion shares.

Speaking to Radiance, the national president of the Welfare Party of India, Dr SQR Ilyas said the party welcomed it and the results were very shocking, adding that it was unfortunate that there had been no such survey since 1931. He said that for a better understanding of the socio-economic equations of various castes, as well as to pass on the benefits of affirmative action to the marginalised sections and to facilitate them to have a socio-political share, caste census is essential. WPI demanded that it should be conducted at a pan-India level along with the national Census.

Vice President, Jamaat-e-Islami Hind, Malik Motasim Khan told Radiance, that in his opinion, “The report will reveal the full picture of how many castes have achieved socio-economic progress and will show the extent of socio-economic deprivation. This will benefit and empower the castes who have been deprived till today. Caste divisions, when they are used to humiliate or exploit people are dangerous. However, this Census is for enabling educational, economic and social uplift of deprived castes.”

He also added, “Particularly in the Hindi-speaking belt of India, casteism, social hierarchy and the existence of zaat-biradari practices is a bitter social reality. In the Islamic framework, tribal or social identities should be limited to mere identification, not leading to any hierarchy or superiority. People ought to be judged only on their deeds. All over the country, Muslims are socially, educationally and economically backward. JIH wants the existing caste divisions among Indian Muslims to be eliminated. If the state provides educational and economic support to deprived communities, there is a possibility that some Muslim groups will at least benefit from this exercise. This is why JIH demands that the state should provide security and support to the marginalised sections among Muslims by way of welfare schemes. JIH will continue to work ideologically and morally for the dignity and respect of people, rather than reinforcing social hierarchy and inequality.”

Who will Benefit?

Who will the caste census results benefit? Will it be of any use to Muslims, especially ‘Pasmanda’ Muslims? Will the BJP benefit from it, or will it lead to a strengthening in social justice politics? All these questions are up in the air as we speak. It all depends on who mobilizes around this data and how.

Ali Anwar Ansari who has written a booklet titled ‘Sampradayik Dhruvikaran Ka Yahi Ilaj, Jati Janganana Ke Liye Ho Jao Taiyar’ meaning ‘Get ready for caste census, this is the solution to communal polarisation’, sees the Census as an answer to the politics of binary polarization that the BJP is seeking to benefit from.

A social worker from Darbhanga who wished to remain anonymous told Radiance that it is first imperative that Muslims accept that caste-based discrimination is a reality, and then they should play an active role on two fronts – to fight caste-based injustices everywhere, and to limit themselves to their own domain and secondly, to ensure the fruits of affirmative action get into the right and deserving hands by way of continuous monitoring of reservation policies. He also argued that the pitfall of centering social justice only around affirmative actions is that a few take advantage while others are left behind; and to quote Paolo Freire, there is always the risk of an oppressed turning into an oppressor, which can also be seen in how some Dalit leaders do not wish to include Dalit Muslims and Dalit Christians in the SC list.

An increased percentage of reservations is a distinct possibility for Muslims, if this data is to be turned into a policy change. It has also already had a ripple effect in other states – with a possibility that the report of Karnataka’s survey will be tabled soon, as CM Siddaramaiah has already promised to accept and implement the data. Will this butterfly effect be a new ‘Mandal-Kamandal’ moment? Only time will tell.

Some of the direct possible outcomes of the caste census results can include – Opposition parties demanding the removal of the 50 percent cap on reservation to educational institutions and government jobs imposed by the Supreme Court, an overall increase and reservation in accordance with the actual share of SC, ST and OBC reservation, and the extension of OBC reservation to legislative bodies.

Another hope is that at a time when ruling right-wing leaders have been positing an 80% (alleged) Hindu majority against a Muslim minority, this new ‘85-25’ can be a pushback against the politics of polarization and hate. A lot depends on who mobilizes around this result, and how.